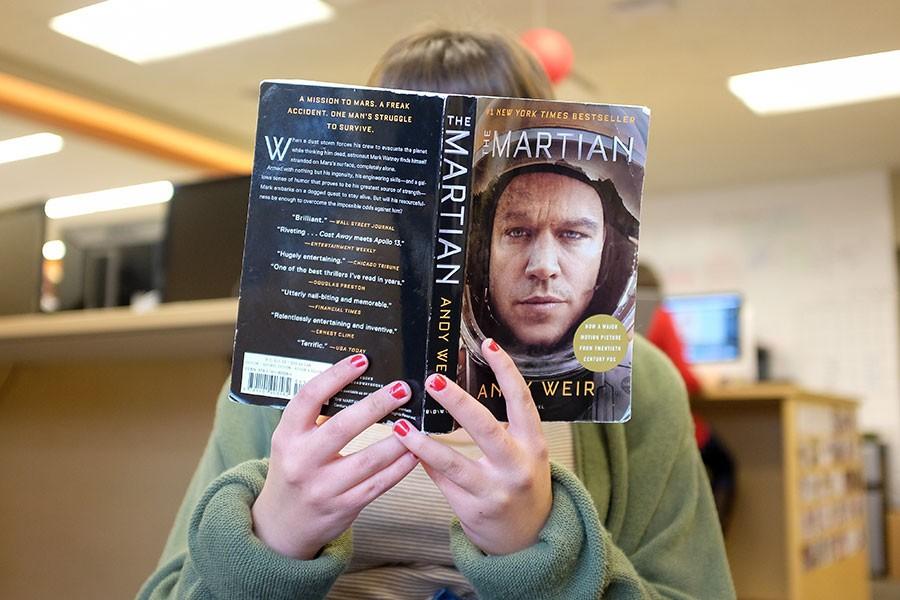

Starting the year in Mars: Reporter reviews Read Across Lawrence novel, “The Martian”

“The Martian” was published in 2011 and made into a movie in 2013. The novel has been highly successful and was chosen as the Read Across Lawrence novel for 2016.

The entire time I was reading Andy Weir’s “The Martian”, I was asking myself how he managed to write such a cohesive novel with heavy research and fully developed characters—and then made it an Academy Award nominee in four years.

Weir’s novel about Mark Watney’s survival on Mars for over a year was the perfect science fiction novel for people who have either never read science fiction, or just don’t enjoy science fiction. Witty, readable and devoid of aliens, “The Martian” was accessible and transitioned to the silver screen with impressive ease.

“The Martian” was at the top of my 2016 to-be-read pile due to its selection as the adult Read Across Lawrence novel, a month long lineup of events relating to the novel sponsored by the Lawrence Public Library. The programs kick-off with the distribution of hundreds of copies of the book, and an evening with professors from KU. It was a solid book to start the year off with. Getting back on the reader’s train takes some work, but “The Martian” didn’t.

Coming from his software engineering background, Weir must have exercised those creative writing muscles like crazy. If I were a software engineer, writing an entire novel wouldn’t exactly be second nature. However, as soon as “The Martian” was finished, Weir was shot into the world of both publishing and filmmaking.

Beginning research around two years earlier, Weir self-published the book in 2011. After reaching incredible success on Amazon, he signed an audiobook contract in 2013 and a print contract with a subdivision of Random House in 2014. Before the print edition even hit stores, “The Martian” was optioned by 20th Century Fox, who premiered the film by October 2015.

That is a pretty tight schedule for someone who just wrote their first novel.

I watched the movie about a month ago and then again right after finishing the book, so separating the two became difficult. But, here’s the thing: it didn’t matter. Both were so similar that the images of Matt Damon parading around in a space suit somewhere in the middle of the sets in Hungary almost perfectly matched what I was reading in the novel.

Often times the big screen crowds out the work that went into the production, but from self-published ebook to academy award nominee, the effort put into “The Martian” is glaring. The science is what makes it stand out. Without the copious amounts of research from Weir, the story wouldn’t seem half as realistic. While most of the science and math went in one ear and out the other, knowing the calculations had been done made it feasible.

Not only is the science the same, almost all of the dialogue is the same as in the novel because a lot of the scientific language can’t be changed—that, and it’s great dialogue. The characters are sharp, nervous, and overworked. I loved it.

The real reason behind “The Martian’s”, however, success is that it seems as if a sandstorm on Mars could sweep up unsuspecting Mark Watney tomorrow. Our technology isn’t too far off, NASA is gaining support again, and all the characters have kids or husbands or hate disco music. Sure, they are all NASA super geniuses, but the key to writing a successful space novel is bringing it back down to earth.

That is where the movie let me down.

At the very end of the novel, Watney was ragged from over a year without a shower and two broken ribs. He looked back on the billions of dollars spent to bring one man back to earth. The overall sentiment was that human nature will always provide help when catastrophe hits, no matter the cost. Light-years apart, the world still felt for their fellow man on Mars.

At the end of the film, Watney is in a classroom. He tells his students that survival is about getting to work, solving one problem after the other until you get to come home.

This was a story about space exploration, potatoes, the human instinct to survive, a whole lot of 70s television shows and the world coming together to help Mark Watney. After reading the book, I didn’t want to see Watney in a classroom, because that’s not the story Weir was trying to tell.